The Spanish Civil War and the Rise of Cyberwar

Posted June 22nd, 2009 by ian99As usual, I greatly enjoyed your blog from 17 June, A Short History of Cyberwar Look-alikes, Rybolov. Moreover I really appreciated your historical examples. It warms my heart whenever an American uses the Russo-Japanese War of 1904/5 as a historic example of anything. Most Americans have never even heard of it. Yet, it is important event today if for no other reason than it established the tradition of having the US President intercede as a peace negotiator and win the Nobel Prize for Peace for his efforts. Because of this, some historians mark it as the historic point at which the US entered the world stage as a great power. By the way the President involved was Teddy Roosevelt.

Concerning the state and nature of Cyberwar today, I’ve seen Rybolov’s models and I think they make sense. Cyberwar as an extension of electronic warfare makes some sense. The analogy does break down at some point because of the peculiarity of the medium. For example, when considering exploitation of SCADA systems as we have seen in the Baltic States and in a less focused manner here in North America, it is hard to see a clear analogy in electronic warfare. The consequences look more like old-fashion kinetic warfare. Likewise, there are aspects of Cyberwarfare that look like good old-fashion human intelligence and espionage. Of course I also have reservations with the electronic warfare model based on government politics. Our friends at NSA have been suggesting that Cyberwarfare is an extension of signals intelligence for years, with the accompanying claim that they (NSA) should have the technical, legal, and of course budgetary resources that go along with it.

I’ve also have seen other writers propose other models of Cyberwarfare and they tend to be a mixed bag at best. At worst, many of the models proposed appear to be the laughable writings of individuals with no more insight to or knowledge of intelligence operations beyond the latest James Bond movie. My own opinion is that two models or driving forces behind international Cyberwarfare activity. The first is pure opportunism. Governments and criminal organizations alike, even authoritarian governments have seen the Hollywood myths and the media hysteria about hacker exploits. Over time, criminal gangs have created and expanded on their cyber capabilities driven by a calculation of profits and risks much like conventional businesses. Combine an international banking environment that allows funds to be transferred across borders with little effort and less time and an international legal environment that is largely out of touch with the Internet and international telecommunications, and we have a breeding ground for Cyber criminals in which the risks of cross-border criminal activity is often much less risky than domestic criminal activity.

As successful Cyber criminal gangs have emerged in totalitarian regimes, it shouldn’t be a surprise that eventually the governments involved would eventually take an interest in both their activities and techniques. There are several reasons that totalitarian government might want to do this. Perhaps the simplest motivation is that the corrupt officials would be drawn to share in the profits in exchange for protection. In addition, the intelligence arms of these nations could also leverage their services and techniques at a fraction of the cost of developing similar capabilities themselves. Additionally, using these capabilities would also provide the intelligence agencies and even the host government with an element of deniability if operations assigned to the criminal gangs were detected.

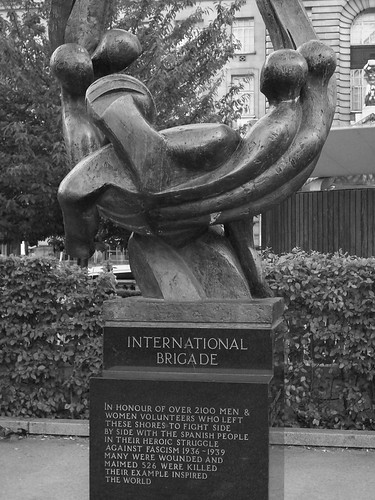

Monument to the International Brigade photo by Secret Pilgrim. For more information, read the history of the International Brigade.

Perhaps the most interesting model of development and Cyberwarfare activity today would be based on the pre-WW II example of the Spanish Civil War. After World War I, a period of mental and societal exhaustion followed on the part of all participating nations. This was quickly follow by a period of self-assessment and rebuilding. In the case of the defeated Germany the reconstruction period protracted due to difficult economic conditions, in part created by the harsh conditions of surrender imposed by the winning European governments.

It was also important to remember that these same victorious European governments undermined many of social and moral underpinnings of German society by systematically all the basis of traditional German government and governmental legitimacy without regard for what should replace it. The assessments of most historians is that these factors combined to sow the seed of hatred against the victorious powers and created a social climate in which a return to open warfare at some time in the future was seen as unavoidable and perhaps desirable. The result was that Germany actively prepared and planned for what was seen as the commonly inevitable war in the future. New systems and technologies were considered, tested. However, treaty limitations also hampered some of these efforts.

In the Soviet Union a similar set of conclusions developed during this period of history within the ruling elite, specifically that renewed war with Germany was inevitable in the near term. Like Germany, the Soviet Union also actively prepared for this war. Likewise they considered and studied new technologies and approaches to war. Somewhat surprisingly, they also secretly conspired with the Germans to provide them with secret proving grounds and test facilities to study some to the new technologies and approaches to war that would otherwise have been banned under provisions of the peace treaties of World War I.

So, when Civil War broke out in Spain in the summer of 1936, both Germany and the Soviet Union were positively delirious at the prospects of testing their new military equipment and theories out under battlefield conditions but, without the risks of participating in a real shooting war as an active belligerent. So, both governments sent every military technology possible to their proxies in Spain under the auspices of “aid”. In some cases they even sent “advisors” who were nothing less than active soldiers and pilots in the conflict. At first, this activity took place under a shroud of secrecy. But, when you send military equipment and people to fight in foreign lands it usually takes no time at all for someone to notice that, “those guys aren’t from here”.

Bomber During the Spanish Civil War photo by -Merce-. Military aviation, bombing in particular, was one of the new technologies that was tested during the Spanish Civil War.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, I think the world has looked at the United States as the world’s sole superpower. Many, view this situation with fear and suspicion. Even some of our former Cold War allies have taken this view. Certainly our primary Cold War adversaries have adopted this stance. If you look at contemporary Chinese and Russian military writing it is clear that they have adopted a position similar to the pre- World War II notion that war between the US and Russia or war between the US and China is inevitable. To make matters worse, during much of the Cold War the US never seemed to pull it together militarily long enough to actually win a war. Toward the end of the Cold War we started smacking smaller allies of the Soviet Union like Grenada and succeeded.

We then moved on to give Iraq a real drubbing after the Cold War. The so-call “Hyperwar” in Iraq terrified the Russians and Chinese alike. The more they studied what we did in Iraq the more terrified they became. On of the many counters they have written about is posing asymmetric threats to the US, that is to say threatening the US in a way in which it is uniquely, or unusually vulnerable. One of these areas of vulnerability is Cyberspace. All sorts of press reporting indicate that the Russians and Chinese have made significant investments in this area. The Russians and Chinese deny these reports as quickly as they emerge. So, it is difficult to determine what the truth is. The fact that the Russians and Chinese are so sensitive to these claims may be a clear indication that they have active programs – the guilty men in these cases have a clear record of protesting to much when they are most guilty.

Assuming that all of this post-Cold War activity is true, I believe this puts us in much the same situation that existed in the pre-World War II Spanish Civil War era. I think the Russian and Chinese governments are just itching to test and refine their Cyberwarfare capabilities. But, at the same time I think they want to operate in a manner similar to how the Germans and the Soviet Union operated in that conflict. I think they want and are testing their capabilities but in a limited way that provides them with some deniability and diplomatic cover. This is important to them because the last thing they want now is to create a Cyber-incident that will precipitate a general conflict or even a major shift in diplomatic or trade relationships.

One of the major differences between the Spanish Civil War example and our current situation of course is that there is no need for a physical battlefield to exist to provide as a live testing environment for Cyber weapons and techniques. However, at least in the case of Russia with respect to Georgia, they are exploiting open military conflicts to use Cyberwar techniques when those conflicts do arise. We have seen similar, but much smaller efforts on the part of Iran, and the Palestinian Authority as embrace what is seen as a cheap and low risk weapon. However, their efforts seem to be more reactionary and rudimentary. The point is, the longer this game goes on without serious consequence the more it will escalate both vertically (in sophistication) and horizontally (be embraced by more countries). Where all of this will lead is anyone guess. But, I think the safe money is betting that the concept of Cyberwar is here to stay and eventually the tools and techniques and full potential of Cyberwar will eventually be used as part of as part of a strategy including more traditional weapons and techniques.

Similar Posts:

Posted in Public Policy, Rants, The Guerilla CISO |  No Comments »

No Comments »

Tags: cybercommand • Cyberwar • FUD • georgia • government • incidentresponse • infosec • publicpolicy • pwnage • risk • security • subversion

Posts RSS

Posts RSS