GAO’s 5 Steps to “Fix” FISMA

Posted July 2nd, 2009 by rybolovLetter from GAO on how Congress can fix FISMA. And oh yeah, the press coverage on it.

Now supposedly this was in response to an inquiry from Congress about “Please comment on the need for improved cyber security relating to S.773, the proposed Cybersecurity Act of 2009.” This is S.773.

GAO is mixing issues and has missed the mark on what Congress asked for. S.773 is all about protecting critical infrastructure. It only rarely mentions government internal IT issues. S.773 has nothing at all to do with FISMA reform. However, GAO doesn’t have much expertise in cybersecurity outside of the Federal Agencies (they have some, but I would never call it extensive), so they reported on what they know.

The GAO report used the often-cited metric of an increase in cybersecurity attacks against Government IT systems growing from “5,503 incidents reported in fiscal year 2006 to 16,843 incidents in fiscal year 2008” as proof that the agencies are not doing anything to fix the problem. I’ve questioned these figures before, it’s associated with the measurement problem and increased reporting requirements more than an increase in attacks. Truth be told, nobody knows if the attacks are increasing and, if so, at what rate. I would guess they’re increasing, but we don’t know, so quit citing some “whacked” metric as proof.

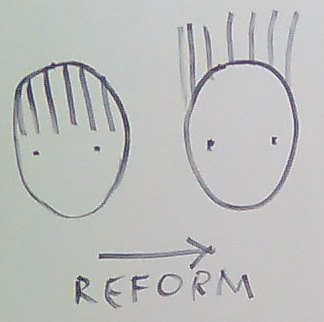

Reform photo by shevy.

GAO’s recommendations for FISMA Reform:

Clarify requirements for testing and evaluating security controls. In other words, the auditing shall continue until the scores improve. Hate to tell you this, but really all you can test at the national level is if the FISMA framework is in place, the execution of the framework (and by extension, if an agency is secure or not) is largely untestable using any kind of a framework.

Require agency heads to provide an assurance statement on the overall adequacy and effectiveness of the agency’s information security program. This is harkening back to the accounting roots of GAO. Basically what we’re talking here is for the agency head to attest that his agency has made the best effort that it can to protect their IT. I like part of this because part of what’s missing is “executive support” for IT security. To be honest, though, most agency heads aren’t IT security dweebs, they would be signing an assurance statement based upon what their CIO/CISO put in the executive summary.

Enhance independent annual evaluations. This has significant cost implications. Besides, we’re getting more and more evaluations as time goes on with an increase in audit burden. IE, in the Government IT security space, how much of your time is spent providing proof to auditors versus building security? For some people, it’s their full-time job.

Strengthen annual reporting mechanisms. More reporting. I don’t think it needs to get strengthened, I think it needs to get “fixed”. And by “fixed” I mean real metrics. I’ve touched on this at least a hundred times, go check out some of it….

Strengthen OMB oversight of agency information security programs. This one gives me brain-hurt. OMB has exactly the amount of oversight that they need to do their job. Just like more auditing, if you increase the oversight and the people doing the execution have the same amount of people and the same amount of funding and the same types of skills, do you really expect them to perform differently?

Rybolov’s synopsis:

When the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail, and I think that’s what GAO is doing here. Since performance in IT security is obviously down, they suggest that more auditing and oversight will help. But then again, at what point does the audit burden tip to the point where nobody is really doing any work at all except for answering to audit requests?

Going back to what Congress really asked for, We run up against a problem. There isn’t a huge set of information about how the rest of the nation is doing with cybersecurity. There’s the Verizon DBIR, the Data Loss DB, some surveys, and that’s about it.

So really, when you ask GAO to find out what the national cybersecurity situation is, all you’re going to get is a bunch of information about how government IT systems line up and maybe some anecdotes about critical infrastructure.

Coming to a blog near you (hopefully soon): Rybolov’s 5 steps to “fix” FISMA.

Similar Posts:

Posted in FISMA |  2 Comments »

2 Comments »

Tags: accounting • accreditation • auditor • catalogofcontrols • certification • compliance • fisma • FUD • gao • government • infosec • itsatrap • management • metrics • omb • S773 • security

Posts RSS

Posts RSS