Rybolov Note: this is such a long blog post that I’m breaking it down into parts. Go read the bill here. Go read part two here. Go read part three here. Go read part four here. Go read part 5 here. =)

So the Library of Congress finally got S.773 up on http://thomas.loc.gov/. For those of you who have been hiding under a rock, this is the Cybersecurity Act of 2009 and is a bill introduced by Senators Rockefeller and Snowe and, depending on your political slant, will allow us to “sock it to the hackers and send them to a federal pound-you-in-the-***-prison” or “vastly erode our civil liberties”.

A little bit of pre-reading is in order:

Timing: Now let’s talk about the timing of this bill. There is the 60-day Cybersecurity Review that is supposed to be coming out Real Soon Now (TM). This bill is an attempt by Congress to head it off at the pass.

Rumor mill says that not only will the Cybersecurity Review be unveiled at RSA (possible, but strange) and that it won’t bring anything new to the debate (more possibly, but then again, nothing’s really new, we’ve known about this stuff for at least a decade).

Overall Comments:

This bill is big. It really is an omnibus Cybersecurity Act and has just about everything you could want and more. There’s a fun way of doing things in the Government, and it goes something like this: ask for 300% of what you need so that you will end up with 80%. And I see this bill is taking this approach to heart.

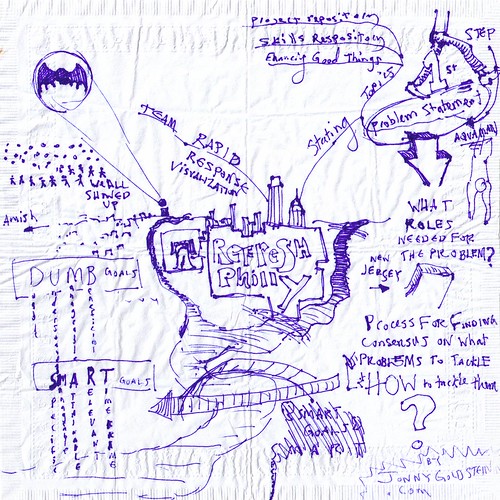

Pennsylvania Ave – Old Post Office to the Capitol at Night photo by wyntuition.

And now for the good, bad, and ugly:

SEC. 2. FINDINGS. This section is primarily a summary of testimony that has been delivered over the past couple of years. It really serves as justification for the rest of the bill. It is a little bit on the FUD side of things (as in “omigod, they put ‘Cyber-Katrina‘ in a piece of legislation”), but overall it’s pretty balanced and what you would expect for a bill. Bottom line here is that we depend on our data and the networks that carry it. Even if you don’t believe in Cyberwar (I don’t really believe in Cyberwar unles it’s just one facet of combined arms warfare), you can probably agree that the costs of insecurity on a macroeconomic scale need to be looked at and defended against, and our dependency on the data and networks is only going to increase.

No self-respecting security practitioner will like this section, but politicians will eat it up. Relax, guys, you’re not the intended audience.

Verdict: Might as well keep this in there, it’s plot development without any requirements.

SEC. 3. CYBERSECURITY ADVISORY PANEL. This section creates a Cybersecurity Advisory Panel made up of Federal Government, private sector, academia, and state and local government. This is pretty typical so far. The interesting thing to me is “(7) whether societal and civil liberty concerns are adequately addressed”… in other words, are we balancing security with citizens’, corporations’, and states’ rights? More to come on this further down in the bill.

Verdict: Will bring a minimal cost in Government terms. I’m very hesitant to create new committees. But yeah, this can stay.

SEC. 4. REAL-TIME CYBERSECURITY DASHBOARD. This section is very interesting to me. On one hand, it’s what we do at the enterprise level for most companies. On the other hand, this is specific to the Commerce Department –“Federal Government information systems and networks managed by the Department of Commerce.” The first reading of this is the internal networks that are internal to Commerce, but then why is this not handed down to all agencies? I puzzled on this and did some research until I remembered that Commerce, through NTIA, runs DNS, and Section 8 contains a review of the DNS contracts.

Verdict: I think this section needs a little bit of rewording so that the scope is clearer, but sure, a dashboard is pretty benign, it’s the implied tasks to make a dashboard function (ie, proper management of IT resources and IT security) that are going to be the hard parts. Rescope the dashboard and explicitly say what kind of information it needs to address and who should receive it.

SEC. 5. STATE AND REGIONAL CYBERSECURITY ENHANCEMENT PROGRAM. This section calls for Regional Cybersecurity Centers, something along the lines of what we call “Centers of Excellence” in the private sector. This section is interesting to me, mostly because of how vague it seemed the first time I read it, but the more times I look at it, I go “yeah, that’s actually a good idea”. What this section tries to do is to bridge the gap between the standards world that is NIST and the people outside of the beltway–the “end-users” of the security frameworks, standards, tools, methodologies, what-the-heck-ever-you-want-to-call-them. Another interesting thing about this is that while the proponent department is Commerce, NIST is part of Commerce, so it’s not as left-field as you might think.

Verdict: While I think this section is going to take a long time to come to fruition (5+ years before any impact is seen), I see that Regional Cybersecurity Centers, if properly funded and executed, can have a very significant impact on the rest of the country. It needs to happen, only I don’t know what the cost is going to be, and that’s the part that scares me.

SEC. 6. NIST STANDARDS DEVELOPMENT AND COMPLIANCE. This is good. Basically this section provides a mandate for NIST to develop a series of standards. Some of these have been sitting around for some time in various incarnations, I doubt that anyone would disagree that these need to be done.

- CYBERSECURITY METRICS RESEARCH: Good stuff. Yes, this needs help. NIST are the people to do this kind of research.

- SECURITY CONTROLS: Already existing in SP 800-53. Depending on interpretation, this changes the scope and language of the catalog of controls to non-Federal IT systems, or possibly a fork of the controls catalog.

- SOFTWARE SECURITY: I guess if it’s in a law, it has come of age. This is one of the things that NIST has wanted to do for some time but they haven’t had the manpower to get involved in this space.

- SOFTWARE CONFIGURATION SPECIFICATION LANGUAGE: Part of SCAP. The standard is there, it just needs to be extended to various pieces of software.

- STANDARD SOFTWARE CONFIGURATION: This is the NIST configuration checklist program ala SP 800-70. I think NIST ran short on manpower for this also and resorted back to pointing at the DISA STIGS and FDCC. This so needs further development into a uniform set of standards and then, here’s the key, rolled back upstream to the software vendors so they ship their product pre-configured.

- VULNERABILITY SPECIFICATION LANGUAGE: Sounds like SCAP.

Now for the “gotchas”:

(d) COMPLIANCE ENFORCEMENT- The Director shall–

(1) enforce compliance with the standards developed by the Institute under this section by software manufacturers, distributors, and vendors; and

(2) shall require each Federal agency, and each operator of an information system or network designated by the President as a critical infrastructure information system or network, periodically to demonstrate compliance with the standards established under this section.

This section basically does 2 things:

- Mandates compliancy for vendors and distributors with the NIST standards listed above. Suprised this hasn’t been talked about elsewhere. This clause suffers from scope problems because if you interpret it BSOFH-stylie, you can take it to mean that anybody who sells a product, regardless of who’s buying, has to sell a securely-configured version. IE, I can’t sell XP to blue-haired grandmothers unless I have something like an FDCC variant installed on it. I mostly agree with this in the security sense but it’s a serious culture shift in the practical sense.

- Mandates an auditing scheme for Federal agencies and critical infrastructure. Everybody’s talked about this, saying that since designation of critical infrastructure is not defined, this is left at the discretion of the Executive Branch. This isn’t as wild-west as the bill’s opponents want it to seem, there is a ton of groundwork layed out in HSPD-7. But yeah, HSPD-7 is an executive directive and can be changed “at the whim” of the President. And yes, this is auditing by Commerce, which has some issues in that Commerce is not equipped to deal with IT security auditing. More on this in a later post.

Verdict: The standard part is already happening today, this section just codifies it and justify’s NIST’s research. Don’t task Commerce with enforcement of NIST standards, it leads down all sorts of inappropriate roads.

Similar Posts:

No Comments »

No Comments » Posts RSS

Posts RSS