Random Thoughts on “The FISMA Challenge” in eHealthcare

Posted August 4th, 2009 by rybolovOK, so there’s this article being bounced all over the place. Basic synopsis is that FISMA is keeping the government from doing any kind of electronic health records stuff because FISMA requirements extend to health care providers and researchers when they take data from the Government.

Read one version of the story here

So the whole solution is that, well, we can’t extend FISMA to eHealthcare when the data is owned by the Government because that security management stuff gets in the way. And this post is about why they’re wrong and right, but not in the places that they think they are.

Government agencies need to protect the data that they have by providing “adequate security”. I’ve covered this a bazillion places already. Somewhere somehow along the lines we let the definition of adequate security mean “You have to play by our rulebook” which is complete and utter bunk. The framework is an expedient and a level-setting experience across the government. It’s not made to be one-size-fits-all, but is instead meant to be tailored to each individual case.

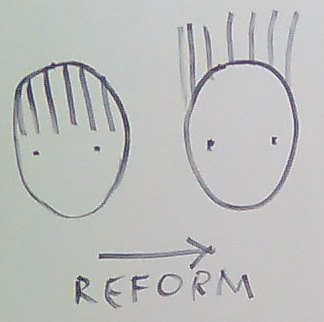

The Government Information Security Trickle-Down Effect is a name I use for FISMA/NIST Framework requirements being transferred from the Government to service providers, whether they’re in healthcare or IT or making screws that sometimes can be used on the B2 bombers. It will hit you if you take Government data but only because you have no regulatory framework of your own with which you can demonstrate that you have “adequate security”. In other words, if you provide a demonstrable level of data protection equal to or superior to what the Government provides, then you should reasonably be able to take the Government data, it’s finding the right “esperanto” to demonstrate your security foo.

If only there was a regulatory scheme already in place that we could use to hold the healthcare industry to. Oh wait, there is: HIPAA. Granted, HIPAA doesn’t really have a lot of teeth and its effects are maybe demonstrable, but it does fill most of the legal requirement to provide “adequate security”, and that’s what’s the important thing, and more importantly, what is required by FISMA.

And this is my problem with this whole string of articles: The power vacuum has claimed eHealthcare. Seriously, there should be somebody who is in charge of the data who can make a decision on what kinds of protections that they want for it. In this case, there are plenty of people with different ideas on what that level of protection is so they are asking OMB for an official ruling. If you go to OMB asking for their guidance on applying FISMA to eHealthcare records, you get what you deserve, which is a “Yes, it’s in scope, how do you think you should do this?”

So what the eHealthcare people really are looking for is a set of firm requirements from their handlers (aka OMB) on how to hold service providers accountable for the data that they are giving them. This isn’t a binary question on whether FISMA applies to eHealthcare data (yes, it does), it’s a question of “how much is enough?” or even “what level of compensating controls do we need?”

But then again, we’re beaten down by compliance at this point. I know I feel it from time to time. After you’ve been beaten badly for years, all you want to do is for the batterer to tell you what you need to do so the hurting will stop.

So for the eHealthcare agencies, here is a solution for you. In your agreements/contracts to provide data to the healthcare providers, require the following:

- Provider shall produde annual statements for HIPAA compliance

- Provider shall be certified under a security management program such as an ISO 27001, SAS-70 Type II, or even PCI-DSS

- Provider shall report any incident resulting in a potential data breach of 500 or more records within 24 hours

- Financial penalties for data breaches based on number of records

- Provider shall allow the Government to perform risk assessments of their data protection controls

That should be enough compensating controls to provide “adequate security” for your eHealthcare data. You can even put a line through some of these that are too draconian or high-cost. Take that to OMB and tell them how you’re doing it and how they would like to spend the taxpayers’ money to do anything other than this.

Case Files and Medical Records photo by benuski.

Similar Posts:

Posted in FISMA, Rants |  1 Comment »

1 Comment »

Tags: compliance • FUD • government • infosec • infosharing • itsatrap • management • omb • security

Posts RSS

Posts RSS