Scenario: American Internet connections are attacked. In the resulting chaos, the Government fails to respond at all, primarily because of infighting over jurisdiction issues between responders. Mass hysteria ensues–40 years of darkness, cats sleeping with dogs kind of stuff.

Sounds similar to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina? Well, this now has a name: Cyber-Katrina.

At least, this is what Paul Kurtz talked about this week at Black Hat DC. Now I understand what Kurtz is saying: that we need to figure out the national-level response while we have time so that when it happens we won’t be frozen with bureaucratic paralysis. Yes, it works for me, I’ve been saying it ever since I thought I was somebody important last year. =)

But Paul…. don’t say you want to create a new Cyber-FEMA for the Internet. That’s where the metaphor you’re using failed–if you carry it too far, what you’re saying is that you want to make a Government organization that will eventually fail when the nation needs it the most. Saying you want a Cyber-FEMA is just an ugly thing to say after you think about it too long.

What Kurtz really meant to say is that we don’t have a national-level CERT that coordinates between the major players–DoD, DoJ, DHS, state and local governments, and the private sector for large-scale incident response. What’s Kurtz is really saying if you read between the lines is that US-CERT needs to be a national-level CERT and needs funding, training, people, and connections to do this mission. In order to fulfill what the administration wants, needs, and is almost promising to the public through their management agenda, US-CERT has to get real big, real fast.

But the trick is, how do you explain this concept to somebody who doesn’t have either the security understanding or the national policy experience to understand the issue? You resort back to Cyber-Katrina and maybe bank on a little FUD in the process. Then the press gets all crazy on it–like breaking SSL means Cyber-Katrina Real Soon Now.

Now for those of you who will never be a candidate for Obama’s Cybersecurity Czar job, let me break this down for you big-bird stylie. Right now there are 3 major candidates vying to get the job. Since there is no official recommendation (and there probably won’t be until April when the 60 days to develop a strategy is over), the 3 candidates are making their move to prove that they’re the right person to pick. Think of it as their mini-platforms, just look out for when they start talking about themselves in the 3rd person.

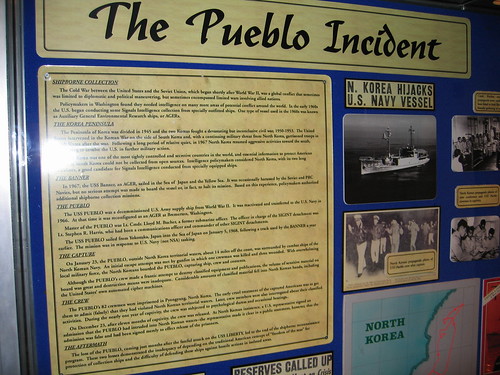

FEMA Disaster Relief photo by Infrogmation. Could a Cyber-FEMA coordinate incident response for a Cyber-Katrina?

And in other news, I3P (with ties to Dartmouth) has issued their National Cyber Security Research and Development Challenges document which um… hashes over the same stuff we’ve seen from the National Strategy to Secure Cyberspace, the Systems and Technology Research and Design Plan, the CSIS Recommendations, and the Obama Agenda. Only the I3P report has all this weird psychologically-oriented mumbo-jumbo that when I read it my eyes glazed over.

Guys, I’ve said this so many times I feel like a complete cynic: talk is cheap, security isn’t. It seems like everybody has a plan but nobody’s willing to step up and fix the problem. Not only that, but they’re taking each others recommendations, throwing them in a blender, and reissuing their own. Wake me up when somebody actually does something.

It leads me to believe that, once again, those who talk don’t know, and those who know don’t talk.

Therefore, here’s the BSOFH’s guide to protecting the nation from Cyber-Katrina:

- Designate a Cybersecurity Czar

- Equip the Cybersecurity Czar with an $100B/year budget

- Nationalize Microsoft, Cisco, and one of the major all-in-one security companies (Symantec)

- Integrate all the IT assets you now own and force them to write good software

- Public execution of any developer who uses strcpy() because who knows what other stupid stuff they’ll do

- Require code review and vulnerability assessments for any IT product that is sold on the market

- Regulate all IT installations to follow Government-approved hardening guides

- Use US-CERT to monitor the military-industrial complex

- ?????

- Live in a secure Cyber-World

But hey, that’s not the American way–we’re not socialists, damnit! (well, except for mortgage companies and banks and automakers and um yeah….) So far all the plans have called for cooperation with the public sector, and that’s worked out just smashingly because of an industry-wide conflict of interest–writing junk software means that you can sell for upgrades or new products later.

I think the problem is fixable, but I predict these are the conditions for it to happen:

- Massive failure of some infrastructure component due to IT security issues

- Massive ownage of Government IT systems that actually gets publicized

- Deaths caused by massive IT Security fail

- Osama Bin Laden starts writing exploit code

- Citizen outrage to the point where my grandmother writes a letter to the President

Until then, security issues will be always be a second-fiddle to wars, the economy, presidential impeachments, and a host of a bazillion other things. Because of this, security conditions will get much, much worse before they get better.

And then the cynic in me can’t help but think that, deep down inside, what the nation needs is precisely an IT Security Fail along the lines of 9-11/Katrina/Pearl Harbor/Dien Bien Fu/Task Force Smith.

Similar Posts:

3 Comments »

3 Comments » Posts RSS

Posts RSS